Friday, 24 August 2018

revelation21

Revelation 21 King James Version (KJV)

21 And I saw a new heaven and a new earth: for the first heaven and the first earth were passed away; and there was no more sea.

2 And I John saw the holy city, new Jerusalem, coming down from God out of heaven, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband.

3 And I heard a great voice out of heaven saying, Behold, the tabernacle of God is with men, and he will dwell with them, and they shall be his people, and God himself shall be with them, and be their God.

4 And God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes; and there shall be no more death, neither sorrow, nor crying, neither shall there be any more pain: for the former things are passed away.

5 And he that sat upon the throne said, Behold, I make all things new. And he said unto me, Write: for these words are true and faithful.

6 And he said unto me, It is done. I am Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end. I will give unto him that is athirst of the fountain of the water of life freely.

7 He that overcometh shall inherit all things; and I will be his God, and he shall be my son.

8 But the fearful, and unbelieving, and the abominable, and murderers, and whoremongers, and sorcerers, and idolaters, and all liars, shall have their part in the lake which burneth with fire and brimstone: which is the second death.

9 And there came unto me one of the seven angels which had the seven vials full of the seven last plagues, and talked with me, saying, Come hither, I will shew thee the bride, the Lamb's wife.

10 And he carried me away in the spirit to a great and high mountain, and shewed me that great city, the holy Jerusalem, descending out of heaven from God,

11 Having the glory of God: and her light was like unto a stone most precious, even like a jasper stone, clear as crystal;

12 And had a wall great and high, and had twelve gates, and at the gates twelve angels, and names written thereon, which are the names of the twelve tribes of the children of Israel:

13 On the east three gates; on the north three gates; on the south three gates; and on the west three gates.

14 And the wall of the city had twelve foundations, and in them the names of the twelve apostles of the Lamb.

15 And he that talked with me had a golden reed to measure the city, and the gates thereof, and the wall thereof.

16 And the city lieth foursquare, and the length is as large as the breadth: and he measured the city with the reed, twelve thousand furlongs. The length and the breadth and the height of it are equal.

17 And he measured the wall thereof, an hundred and forty and four cubits, according to the measure of a man, that is, of the angel.

18 And the building of the wall of it was of jasper: and the city was pure gold, like unto clear glass.

19 And the foundations of the wall of the city were garnished with all manner of precious stones. The first foundation was jasper; the second, sapphire; the third, a chalcedony; the fourth, an emerald;

20 The fifth, sardonyx; the sixth, sardius; the seventh, chrysolyte; the eighth, beryl; the ninth, a topaz; the tenth, a chrysoprasus; the eleventh, a jacinth; the twelfth, an amethyst.

21 And the twelve gates were twelve pearls: every several gate was of one pearl: and the street of the city was pure gold, as it were transparent glass.

22 And I saw no temple therein: for the Lord God Almighty and the Lamb are the temple of it.

23 And the city had no need of the sun, neither of the moon, to shine in it: for the glory of God did lighten it, and the Lamb is the light thereof.

24 And the nations of them which are saved shall walk in the light of it: and the kings of the earth do bring their glory and honour into it.

25 And the gates of it shall not be shut at all by day: for there shall be no night there.

26 And they shall bring the glory and honour of the nations into it.

27 And there shall in no wise enter into it any thing that defileth, neither whatsoever worketh abomination, or maketh a lie: but they which are written in the Lamb's book of life.

King James Version (KJV)

revelation 22

Revelation 22 New International Version (NIV)

Eden Restored

22 Then the angel showed me the river of the water of life, as clear as crystal, flowing from the throne of God and of the Lamb 2 down the middle of the great street of the city. On each side of the river stood the tree of life, bearing twelve crops of fruit, yielding its fruit every month. And the leaves of the tree are for the healing of the nations. 3 No longer will there be any curse. The throne of God and of the Lamb will be in the city, and his servants will serve him. 4 They will see his face, and his name will be on their foreheads. 5 There will be no more night. They will not need the light of a lamp or the light of the sun, for the Lord God will give them light. And they will reign for ever and ever.

John and the Angel

6 The angel said to me, “These words are trustworthy and true. The Lord, the God who inspires the prophets, sent his angel to show his servants the things that must soon take place.”

7 “Look, I am coming soon! Blessed is the one who keeps the words of the prophecy written in this scroll.”

8 I, John, am the one who heard and saw these things. And when I had heard and seen them, I fell down to worship at the feet of the angel who had been showing them to me. 9 But he said to me, “Don’t do that! I am a fellow servant with you and with your fellow prophets and with all who keep the words of this scroll. Worship God!”

10 Then he told me, “Do not seal up the words of the prophecy of this scroll, because the time is near. 11 Let the one who does wrong continue to do wrong; let the vile person continue to be vile; let the one who does right continue to do right; and let the holy person continue to be holy.”

Epilogue: Invitation and Warning

12 “Look, I am coming soon! My reward is with me, and I will give to each person according to what they have done. 13 I am the Alpha and the Omega, the First and the Last, the Beginning and the End.

14 “Blessed are those who wash their robes, that they may have the right to the tree of life and may go through the gates into the city. 15 Outside are the dogs, those who practice magic arts, the sexually immoral, the murderers, the idolaters and everyone who loves and practices falsehood.

16 “I, Jesus, have sent my angel to give you[a] this testimony for the churches. I am the Root and the Offspring of David, and the bright Morning Star.”

17 The Spirit and the bride say, “Come!” And let the one who hears say, “Come!” Let the one who is thirsty come; and let the one who wishes take the free gift of the water of life.

18 I warn everyone who hears the words of the prophecy of this scroll: If anyone adds anything to them, God will add to that person the plagues described in this scroll. 19 And if anyone takes words away from this scroll of prophecy, God will take away from that person any share in the tree of life and in the Holy City, which are described in this scroll.

20 He who testifies to these things says, “Yes, I am coming soon.”

Amen. Come, Lord Jesus.

21 The grace of the Lord Jesus be with God’s people. Amen.

Footnotes:

Saturday, 18 August 2018

HEBREWS 11

Hebrews 11 King James Version (KJV)

11 Now faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.

2 For by it the elders obtained a good report.

3 Through faith we understand that the worlds were framed by the word of God, so that things which are seen were not made of things which do appear.

4 By faith Abel offered unto God a more excellent sacrifice than Cain, by which he obtained witness that he was righteous, God testifying of his gifts: and by it he being dead yet speaketh.

5 By faith Enoch was translated that he should not see death; and was not found, because God had translated him: for before his translation he had this testimony, that he pleased God.

6 But without faith it is impossible to please him: for he that cometh to God must believe that he is, and that he is a rewarder of them that diligently seek him.

7 By faith Noah, being warned of God of things not seen as yet, moved with fear, prepared an ark to the saving of his house; by the which he condemned the world, and became heir of the righteousness which is by faith.

8 By faith Abraham, when he was called to go out into a place which he should after receive for an inheritance, obeyed; and he went out, not knowing whither he went.

9 By faith he sojourned in the land of promise, as in a strange country, dwelling in tabernacles with Isaac and Jacob, the heirs with him of the same promise:

10 For he looked for a city which hath foundations, whose builder and maker is God.

11 Through faith also Sara herself received strength to conceive seed, and was delivered of a child when she was past age, because she judged him faithful who had promised.

12 Therefore sprang there even of one, and him as good as dead, so many as the stars of the sky in multitude, and as the sand which is by the sea shore innumerable.

13 These all died in faith, not having received the promises, but having seen them afar off, and were persuaded of them, and embraced them, and confessed that they were strangers and pilgrims on the earth.

14 For they that say such things declare plainly that they seek a country.

15 And truly, if they had been mindful of that country from whence they came out, they might have had opportunity to have returned.

16 But now they desire a better country, that is, an heavenly: wherefore God is not ashamed to be called their God: for he hath prepared for them a city.

17 By faith Abraham, when he was tried, offered up Isaac: and he that had received the promises offered up his only begotten son,

18 Of whom it was said, That in Isaac shall thy seed be called:

19 Accounting that God was able to raise him up, even from the dead; from whence also he received him in a figure.

20 By faith Isaac blessed Jacob and Esau concerning things to come.

21 By faith Jacob, when he was a dying, blessed both the sons of Joseph; and worshipped, leaning upon the top of his staff.

22 By faith Joseph, when he died, made mention of the departing of the children of Israel; and gave commandment concerning his bones.

23 By faith Moses, when he was born, was hid three months of his parents, because they saw he was a proper child; and they were not afraid of the king's commandment.

24 By faith Moses, when he was come to years, refused to be called the son of Pharaoh's daughter;

25 Choosing rather to suffer affliction with the people of God, than to enjoy the pleasures of sin for a season;

26 Esteeming the reproach of Christ greater riches than the treasures in Egypt: for he had respect unto the recompence of the reward.

27 By faith he forsook Egypt, not fearing the wrath of the king: for he endured, as seeing him who is invisible.

28 Through faith he kept the passover, and the sprinkling of blood, lest he that destroyed the firstborn should touch them.

29 By faith they passed through the Red sea as by dry land: which the Egyptians assaying to do were drowned.

30 By faith the walls of Jericho fell down, after they were compassed about seven days.

31 By faith the harlot Rahab perished not with them that believed not, when she had received the spies with peace.

32 And what shall I more say? for the time would fail me to tell of Gedeon, and of Barak, and of Samson, and of Jephthae; of David also, and Samuel, and of the prophets:

33 Who through faith subdued kingdoms, wrought righteousness, obtained promises, stopped the mouths of lions.

34 Quenched the violence of fire, escaped the edge of the sword, out of weakness were made strong, waxed valiant in fight, turned to flight the armies of the aliens.

35 Women received their dead raised to life again: and others were tortured, not accepting deliverance; that they might obtain a better resurrection:

36 And others had trial of cruel mockings and scourgings, yea, moreover of bonds and imprisonment:

37 They were stoned, they were sawn asunder, were tempted, were slain with the sword: they wandered about in sheepskins and goatskins; being destitute, afflicted, tormented;

38 (Of whom the world was not worthy:) they wandered in deserts, and in mountains, and in dens and caves of the earth.

39 And these all, having obtained a good report through faith, received not the promise:

40 God having provided some better thing for us, that they without us should not be made perfect.

1 PETER 1

Praise to God for a Living Hope

3 Praise be to the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ! In his great mercy he has given us new birth into a living hope through the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead, 4 and into an inheritance that can never perish, spoil or fade. This inheritance is kept in heaven for you, 5 who through faith are shielded by God’s power until the coming of the salvation that is ready to be revealed in the last time. 6 In all this you greatly rejoice, though now for a little while you may have had to suffer grief in all kinds of trials. 7 These have come so that the proven genuineness of your faith—of greater worth than gold, which perishes even though refined by fire—may result in praise, glory and honor when Jesus Christ is revealed. 8 Though you have not seen him, you love him; and even though you do not see him now, you believe in him and are filled with an inexpressible and glorious joy, 9 for you are receiving the end result of your faith, the salvation of your souls.

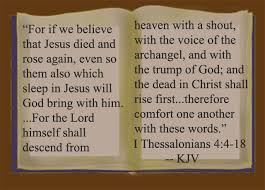

1 THESSALONIANS 4

Thessalonians 4

1

Finally, brothers, we instructed you how to live in order to please God, as in fact you are living. Now we ask you and urge you in the Lord Jesus to do this more and more.

2

For you know what instructions we gave you by the authority of the Lord Jesus.

3

It is God's will that you should be sanctified: that you should avoid sexual immorality;

4

that each of you should learn to control his own body [1] in a way that is holy and honorable,

5

not in passionate lust like the heathen, who do not know God;

6

and that in this matter no one should wrong his brother or take advantage of him. The Lord will punish men for all such sins, as we have already told you and warned you.

7

For God did not call us to be impure, but to live a holy life.

8

Therefore, he who rejects this instruction does not reject man but God, who gives you his Holy Spirit.

9

Now about brotherly love we do not need to write to you, for you yourselves have been taught by God to love each other.

10

And in fact, you do love all the brothers throughout Macedonia. Yet we urge you, brothers, to do so more and more.

11

Make it your ambition to lead a quiet life, to mind your own business and to work with your hands, just as we told you,

12

so that your daily life may win the respect of outsiders and so that you will not be dependent on anybody.

13

Brothers, we do not want you to be ignorant about those who fall asleep, or to grieve like the rest of men, who have no hope.

14

We believe that Jesus died and rose again and so we believe that God will bring with Jesus those who have fallen asleep in him.

15

According to the Lord's own word, we tell you that we who are still alive, who are left till the coming of the Lord, will certainly not precede those who have fallen asleep.

16

For the Lord himself will come down from heaven, with a loud command, with the voice of the archangel and with the trumpet call of God, and the dead in Christ will rise first.

17

After that, we who are still alive and are left will be caught up together with them in the clouds to meet the Lord in the air. And so we will be with the Lord forever.

18

Therefore encourage each other with these words.

[4] Or learn to live with his own wife; or learn to acquire a wife

2 CORINTHIANS 5

New Bodies

1For we know that when this earthly tent we live in is taken down (that is, when we die and leave this earthly body), we will have a house in heaven, an eternal body made for us by God himself and not by human hands. 2We grow weary in our present bodies, and we long to put on our heavenly bodies like new clothing. 3For we will put on heavenly bodies;we will not be spirits without bodies.5:3 Greek we will not be naked. 4While we live in these earthly bodies, we groan and sigh, but it’s not that we want to die and get rid of these bodies that clothe us. Rather, we want to put on our new bodies so that these dying bodies will be swallowed up by life. 5God himself has prepared us for this, and as a guarantee he has given us his Holy Spirit.

6So we are always confident, even though we know that as long as we live in these bodies we are not at home with the Lord. 7For we live by believing and not by seeing. 8Yes, we are fully confident, and we would rather be away from these earthly bodies, for then we will be at home with the Lord. 9So whether we are here in this body or away from this body, our goal is to please him. 10For we must all stand before Christ to be judged. We will each receive whatever we deserve for the good or evil we have done in this earthly body.

We Are God’s Ambassadors

11Because we understand our fearful responsibility to the Lord, we work hard to persuade others. God knows we are sincere, and I hope you know this, too. 12Are we commending ourselves to you again? No, we are giving you a reason to be proud of us,5:12 Some manuscripts read proud of yourselves. so you can answer those who brag about having a spectacular ministry rather than having a sincere heart. 13If it seems we are crazy, it is to bring glory to God. And if we are in our right minds, it is for your benefit. 14Either way, Christ’s love controls us.5:14a Or urges us on. Since we believe that Christ died for all, we also believe that we have all died to our old life.5:14b Greek Since one died for all, then all died. 15He died for everyone so that those who receive his new life will no longer live for themselves. Instead, they will live for Christ, who died and was raised for them.

16So we have stopped evaluating others from a human point of view. At one time we thought of Christ merely from a human point of view. How differently we know him now! 17This means that anyone who belongs to Christ has become a new person. The old life is gone; a new life has begun!

18And all of this is a gift from God, who brought us back to himself through Christ. And God has given us this task of reconciling people to him. 19For God was in Christ, reconciling the world to himself, no longer counting people’s sins against them. And he gave us this wonderful message of reconciliation. 20So we are Christ’s ambassadors; God is making his appeal through us. We speak for Christ when we plead, “Come back to God!” 21For God made Christ, who never sinned, to be the offering for our sin,5:21 Or to become sin itself. so that we could be made right with God through Christ.

Holy Bible, New Living Translation copyright 1996, 2004, 2007 by Tyndale House Foundation. Used by permission of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., Carol Stream, Illinois, 60188. All rights reserved.

Learn More about the New Living Translation

Friday, 17 August 2018

Matthew 5 JESUS SPOKE THESE WORDS

Matthew 5 King James Version (KJV)

5 And seeing the multitudes, he went up into a mountain: and when he was set, his disciples came unto him:

2 And he opened his mouth, and taught them, saying,

3 Blessed are the poor in spirit: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

4 Blessed are they that mourn: for they shall be comforted.

5 Blessed are the meek: for they shall inherit the earth.

6 Blessed are they which do hunger and thirst after righteousness: for they shall be filled.

7 Blessed are the merciful: for they shall obtain mercy.

8 Blessed are the pure in heart: for they shall see God.

9 Blessed are the peacemakers: for they shall be called the children of God.

10 Blessed are they which are persecuted for righteousness' sake: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

11 Blessed are ye, when men shall revile you, and persecute you, and shall say all manner of evil against you falsely, for my sake.

12 Rejoice, and be exceeding glad: for great is your reward in heaven: for so persecuted they the prophets which were before you.

13 Ye are the salt of the earth: but if the salt have lost his savour, wherewith shall it be salted? it is thenceforth good for nothing, but to be cast out, and to be trodden under foot of men.

14 Ye are the light of the world. A city that is set on an hill cannot be hid.

15 Neither do men light a candle, and put it under a bushel, but on a candlestick; and it giveth light unto all that are in the house.

16 Let your light so shine before men, that they may see your good works, and glorify your Father which is in heaven.

17 Think not that I am come to destroy the law, or the prophets: I am not come to destroy, but to fulfil.

18 For verily I say unto you, Till heaven and earth pass, one jot or one tittle shall in no wise pass from the law, till all be fulfilled.

19 Whosoever therefore shall break one of these least commandments, and shall teach men so, he shall be called the least in the kingdom of heaven: but whosoever shall do and teach them, the same shall be called great in the kingdom of heaven.

20 For I say unto you, That except your righteousness shall exceed the righteousness of the scribes and Pharisees, ye shall in no case enter into the kingdom of heaven.

21 Ye have heard that it was said of them of old time, Thou shalt not kill; and whosoever shall kill shall be in danger of the judgment:

22 But I say unto you, That whosoever is angry with his brother without a cause shall be in danger of the judgment: and whosoever shall say to his brother, Raca, shall be in danger of the council: but whosoever shall say, Thou fool, shall be in danger of hell fire.

23 Therefore if thou bring thy gift to the altar, and there rememberest that thy brother hath ought against thee;

24 Leave there thy gift before the altar, and go thy way; first be reconciled to thy brother, and then come and offer thy gift.

25 Agree with thine adversary quickly, whiles thou art in the way with him; lest at any time the adversary deliver thee to the judge, and the judge deliver thee to the officer, and thou be cast into prison.

26 Verily I say unto thee, Thou shalt by no means come out thence, till thou hast paid the uttermost farthing.

27 Ye have heard that it was said by them of old time, Thou shalt not commit adultery:

28 But I say unto you, That whosoever looketh on a woman to lust after her hath committed adultery with her already in his heart.

29 And if thy right eye offend thee, pluck it out, and cast it from thee: for it is profitable for thee that one of thy members should perish, and not that thy whole body should be cast into hell.

30 And if thy right hand offend thee, cut it off, and cast it from thee: for it is profitable for thee that one of thy members should perish, and not that thy whole body should be cast into hell.

31 It hath been said, Whosoever shall put away his wife, let him give her a writing of divorcement:

32 But I say unto you, That whosoever shall put away his wife, saving for the cause of fornication, causeth her to commit adultery: and whosoever shall marry her that is divorced committeth adultery.

33 Again, ye have heard that it hath been said by them of old time, Thou shalt not forswear thyself, but shalt perform unto the Lord thine oaths:

34 But I say unto you, Swear not at all; neither by heaven; for it is God's throne:

35 Nor by the earth; for it is his footstool: neither by Jerusalem; for it is the city of the great King.

36 Neither shalt thou swear by thy head, because thou canst not make one hair white or black.

37 But let your communication be, Yea, yea; Nay, nay: for whatsoever is more than these cometh of evil.

38 Ye have heard that it hath been said, An eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth:

39 But I say unto you, That ye resist not evil: but whosoever shall smite thee on thy right cheek, turn to him the other also.

40 And if any man will sue thee at the law, and take away thy coat, let him have thy cloak also.

41 And whosoever shall compel thee to go a mile, go with him twain.

42 Give to him that asketh thee, and from him that would borrow of thee turn not thou away.

43 Ye have heard that it hath been said, Thou shalt love thy neighbour, and hate thine enemy.

44 But I say unto you, Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you;

45 That ye may be the children of your Father which is in heaven: for he maketh his sun to rise on the evil and on the good, and sendeth rain on the just and on the unjust.

46 For if ye love them which love you, what reward have ye? do not even the publicans the same?

47 And if ye salute your brethren only, what do ye more than others? do not even the publicans so?

48 Be ye therefore perfect, even as your Father which is in heaven is perfect.

Wednesday, 8 August 2018

JAMES WELDON JOHNSON

James Weldon Johnson FoundationABOUT

JAMES WELDON JOHNSON

ARTISTS-IN-RESIDENCY PROGRAM

NEWS

DONATE CONTACT

Chronology

Biography

James Weldon Johnson was an author, lyricist, poet, diplomat, attorney and leader of the NAACP. He authored the lyrics to Lift Every Voice and Sing, also known as the Black National Anthem. He worked tirelessly for social justice and to expose the power of African-American contributions to the intellectual and artistic life of America.

1871--Born June 17 to James and Helen Louise Dillet Johnson in Jacksonville, Florida.Biography

James Weldon Johnson was an author, lyricist, poet, diplomat, attorney and leader of the NAACP. He authored the lyrics to Lift Every Voice and Sing, also known as the Black National Anthem. He worked tirelessly for social justice and to expose the power of African-American contributions to the intellectual and artistic life of America.

1884-Makes trip to New York City.Biography

James Weldon Johnson was an author, lyricist, poet, diplomat, attorney and leader of the NAACP. He authored the lyrics to Lift Every Voice and Sing, also known as the Black National Anthem. He worked tirelessly for social justice and to expose the power of African-American contributions to the intellectual and artistic life of America.

1886-Meets Frederick Douglass in Jacksonville.

1887-Graduates from Stanton School in Jacksonville. Enters Atlanta University Preparatory Division.

1890-Graduates from Atlanta University Preparatory Division. Enters Atlanta University's freshman class.

1891-Teaches school in Henry County, Georgia, during the summer following his freshman year.

1892-Wins Atlanta University Oratory Prize for "The Best Methods of Removing the Disabilities of Caste from the Negro."

1893-Meets Paul Laurence Dunbar at the Chicago World's Fair.

1894-Receives B. A. degree with honors from Atlanta University. Delivers the valedictory speech, "The Destiny of the Human Race." Tours New England with the Atlanta University Quartet for three months. Is appointed principal of the Stanton School in Jacksonville.

1895-Founds The Daily American, an afternoon daily newspaper serving Jacksonville's black population.

1896-Expands Stanton to high school status, making it the first public high school for blacks in the state of Florida.

1898-Becomes the first African American to be admitted to the Florida bar. Opens a law office with J. Douglas Wetmore.

1900-Writes the lyrics to Lift Every Voice and Sing with music by his brother, J. Rosamond Johnson.

1901-Elected president of the Florida State Teachers Association. Nearly lynched in a Jacksonville park. This near lynching made him realize that he could not advance in the South.

1902-Resigns as principal of Stanton School. Moves to New York to form musical trio with his brother Rosamond and the famous vaudevillian Bob Cole. Becomes the chief lyricist in the Broadway musical team, Cole and the Johnson Brothers. (The trio will write nine songs for Broadway productions.)

1903-Attends graduate school at Columbia University, where he studies with Brander Matthews, professor of dramatic literature.

1904-Writes two songs for Theodore Roosevelt's presidential campaign. Becomes a member of the National Business League, an organization founded by Booker T. Washington. Receives honorary degree from Atlanta University. During this time, he meets W. E. B. Du Bois then a professor at Atlanta University.

1905-Cole and Johnson Brothers go on European tour.

1906-Accepts membership in the Society of International Law. Is appointed U. S. Consul to Venezuela by President Theodore Roosevelt.

1909-Is promoted to U. S. Consul to Corinto, Nicaragua. Is engaged to Grace Elizabeth Nail in October.

1910-Marries Grace Nail, daughter of wealthy New York real estate developer and tavern owner John Bennett Nail, on February 3 at the Nails' family home in New York City.

1912-Publishes anonymously The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man, probably the earliest first-person fictional narrative by an African American.

1913-Resigns from the consular service on account of race prejudice and party politics.

1914-Accepts position as contributing editor to The New York Age. With Irving Berlin, Victor Herbert, and John Philip Sousa, becomes a founding member of the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP). Joins Sigma Pi Phi fraternity and Phi Beta Sigma fraternity.

1915-Becomes member of the NAACP. Puts into English the libretto of Goyescas, the Spanish grand opera, which is produced at the Metropolitan Opera.

1916-Attends the NAACP conference in Amenia, New York, at the estate of J. E. Spingarn. Delivers speech, "A Working Programme for the Future." Joins the staff of the NAACP in the position of field secretary.

1917-Publishes volume Fifty Years and Other Poems. Publishes poem "Saint Peter Relates an Incident of the Resurrection Day." With W. E. B. Du Bois, leads over 15,000 marchers down Fifth Avenue to protest lynchings and riots. Becomes acting secretary of the NAACP. Supports U. S. entry into World War I and fights against the atrocities perpetrated against black soldiers. Meets Walter White in Atlanta and persuades him to join the staff of the NAACP. Attends conference of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society in Bellport, New York, gives talk on the contribution of the Negro to American culture. With W. E. B. Du Bois, becomes a charter member for the Civic Club, a liberal club that grew to be a strong influence in the life of black New Yorkers.

1918-Is responsible for an unprecedented increase in NAACP membership in one year, particularly in the South, making the NAACP a national power.

1919-Participates in converting the National Civil Liberties Bureau into a permanent organization, the American Civil Liberties Union.

1920-NAACP board of directors name him secretary (chief executive officer), making him the first African American to serve in that position. Publishes "Self Determining Haiti" which draws on his earlier investigation of the American occupation there.

1922-Publishes The Book of American Negro Poetry.

1924-Assists several writers of the Harlem Renaissance.

1925-Receives the NAACP's Spingarn Medal. Co-authors with J. Rosamond Johnson The Book of American Negro Spirituals.

1926-Co-authors with J. Rosamond Johnson The Second Book of American Negro Spirituals. Purchases an old farm in the Massachusetts Berkshires and builds a summer cottage called Five Acres.

1927-During the height of the Harlem Renaissance, The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man is reprinted. (The spelling "coloured" was used to enhance British sales.) God's Trombones is published.

1928-Receives Harmon Award for God's Trombones. Receives D. Litt.

from Howard University and Talledega College.

1929-Takes a leave of absence from the NAACP. Travels to Japan to attend the Third Japanese Biennial Conference on Pacific Relations. Receives Julius Rosenwald Fellowship to write Black Manhattan.

1930-Black Manhattan, the story of African Americans in New York from the seventeenth century to the 1920s is published. Resigns from the NAACP December 17.

1931-Publishes the revised edition of The Book of American Negro Poetry. NAACP honors him by hosting a testimonial dinner in New York City attended by over 300 guests. Is appointed vice president and board member of the NAACP. Accepts Fisk University appointment as the Adam K. Spence Professor of Creative Literature.

1933-Publishes autobiography, Along This Way. Attends the second NAACP Amenia Conference.

1934-Is appointed visiting professor, fall semester, at New York University, becoming the first African American to hold such a position at the institution. Receives the Du Bois Prize for Black Manhattan as the best book of prose written by an African American during a three-year period. Publishes Negro Americans, What Now?

1935-Publishes Saint Peter Relates an Incident: Selected Poems.

1936-Board of Directors of Atlanta University offers him the position of president of the university. He declines the offer.

1938-Dies June 26 as a result of an automobile accident in Wiscasset, Maine, nine days after his sixty-seventh birthday. Funeral held at the Salem Methodist Church in Harlem on Thursday, June 30. Is cremated.

*Mrs. James Weldon Johnson (Grace Nail Johnson) died on November 1, 1976, at home in New York City. Grace and James Weldon Johnson were interred together by Ollie Jewel Sims Okala on November 19, 1976, in the John B. Nail family plot in the Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn, New York.

Saturday, 4 August 2018

BOOKER T WASHINGTON

Page semi-protected

Booker T. Washington

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigationJump to search

Booker T. Washington

Booker T Washington retouched flattened-crop.jpg

Booker T. Washington, 1905

Born Booker Taliaferro Washington

c. 1856

Hale's Ford, Virginia, U.S.

Died November 14, 1915 (aged 58–59)

Tuskegee, Alabama, U.S.

Resting place Tuskegee University

Alma mater Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute

Wayland Seminary

Occupation Educator, author, and African American civil rights leader

Political party Republican

Opponent(s) W. E. B. Du Bois

Spouse(s) Fannie N. Smith

(1882–1884, her death)

Olivia A. Davidson

(1886–1889, her death)

Margaret James Murray

(1893–1915, his death)

Children Portia M. Washington

Booker T. Washington Jr.

Ernest Davidson Washington

Signature

Booker T Washington Signature.svg

Booker Taliaferro Washington (c. 1856 – November 14, 1915) was an American educator, author, orator, and advisor to presidents of the United States. Between 1890 and 1915, Washington was the dominant leader in the African-American community.

Page semi-protected

Booker T. Washington

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigationJump to search

Booker T. Washington

Booker T Washington retouched flattened-crop.jpg

Booker T. Washington, 1905

Born Booker Taliaferro Washington

c. 1856

Hale's Ford, Virginia, U.S.

Died November 14, 1915 (aged 58–59)

Tuskegee, Alabama, U.S.

Resting place Tuskegee University

Alma mater Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute

Wayland Seminary

Occupation Educator, author, and African American civil rights leader

Political party Republican

Opponent(s) W. E. B. Du Bois

Spouse(s) Fannie N. Smith

(1882–1884, her death)

Olivia A. Davidson

(1886–1889, her death)

Margaret James Murray

(1893–1915, his death)

Children Portia M. Washington

Booker T. Washington Jr.

Ernest Davidson Washington

Signature

Booker T Washington Signature.svg

Booker Taliaferro Washington (c. 1856 – November 14, 1915) was an American educator, author, orator, and advisor to presidents of the United States. Between 1890 and 1915, Washington was the dominant leader in the African-American community.

Washington was from the last generation of black American leaders born into slavery and became the leading voice of the former slaves and their descendants. They were newly oppressed in the South by disenfranchisement and the Jim Crow discriminatory laws enacted in the post-Reconstruction Southern states in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Washington was a key proponent of African-American businesses and one of the founders of the National Negro Business League. His base was the Tuskegee Institute, a historically black college in Alabama. As lynchings in the South reached a peak in 1895, Washington gave a speech, known as the "Atlanta compromise", which brought him national fame. He called for black progress through education and entrepreneurship, rather than trying to challenge directly the Jim Crow segregation and the disenfranchisement of black voters in the South. Washington mobilized a nationwide coalition of middle-class blacks, church leaders, and white philanthropists and politicians, with a long-term goal of building the community's economic strength and pride by a focus on self-help and schooling. But, secretly, he also supported court challenges to segregation and restrictions on voter registration, passing on funds to the NAACP for this purpose.[1] Black militants in the North, led by W. E. B. Du Bois, at first supported the Atlanta compromise but after 1909, they set up the NAACP to work for political change. They tried with limited success to challenge Washington's political machine for leadership in the black community but also built wider networks among white allies in the North.[2] Decades after Washington's death in 1915, the civil rights movement of the 1950s took a more active and militant approach, which was also based on new grassroots organizations based in the South, such as CORE, SNCC and SCLC.

Booker T. Washington mastered the nuances of the political arena in the late 19th century, which enabled him to manipulate the media, raise money, develop strategy, network, push, reward friends, and distribute funds, while punishing those who opposed his plans for uplifting blacks. His long-term goal was to end the disenfranchisement of the vast majority of African Americans, who then still lived in the South.[3]

Contents

1 Overview

2 Early life

3 Higher education

4 Tuskegee Institute

5 Marriages and children

6 Politics and the Atlanta compromise

7 Wealthy friends and benefactors

7.1 Henry Huttleston Rogers

7.2 Anna T. Jeanes

7.3 Julius Rosenwald

8 Up from Slavery to the White House

9 Death

10 Honors and memorials

11 Legacy

11.1 Descendants

12 Representation in other media

13 Works

14 See also

15 Notes

16 Further reading

16.1 Historiography

16.2 Primary sources

17 External links

Overview

In 1856, Washington was born into slavery in Virginia as the son of Jane, an African-American slave.[4] After emancipation, she moved the family to West Virginia to join her husband Washington Ferguson. As a young man, Washington worked his way through Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute (a historically black college now Hampton University) and attended college at Wayland Seminary (now Virginia Union University). In 1881, Washington was named as the first leader of the new Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, founded for the higher education of blacks.

Washington attained national prominence for his Atlanta Address of 1895, which attracted the attention of politicians and the public. He became a popular spokesperson for African-American citizens. He built a nationwide network of supporters in many black communities, with black ministers, educators, and businessmen composing his core supporters. Washington played a dominant role in black politics, winning wide support in the black community of the South and among more liberal whites (especially rich Northern whites). He gained access to top national leaders in politics, philanthropy and education. Washington's efforts included cooperating with white people and enlisting the support of wealthy philanthropists. Beginning in the 1920s, with the help of Julius Rosenwald, he raised funds to build and operate thousands of new, small rural schools and institutions of higher education to improve education for blacks throughout the South. This work continued for many years after his death. Washington argued that the surest way for blacks to gain equal social rights was to demonstrate "industry, thrift, intelligence and property."

Northern critics called Washington's widespread organization the "Tuskegee Machine". After 1909, Washington was criticized by the leaders of the new NAACP, especially W. E. B. Du Bois, who demanded a stronger tone of protest in order to advance the civil rights agenda. Washington replied that confrontation would lead to disaster for the outnumbered blacks in society, and that cooperation with supportive whites was the only way to overcome pervasive racism in the long run. At the same time, he secretly funded litigation for civil rights cases, such as challenges to southern constitutions and laws that had disenfranchised blacks across the South since the turn of the century.[1][5] African Americans were still strongly affiliated with the Republican Party, and Washington was on close terms with national Republican Party leaders. He was often asked for political advice by presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft.[6]

In addition to his contributions in education, Washington wrote 14 books; his autobiography, Up from Slavery, first published in 1901, is still widely read today. During a difficult period of transition, he did much to improve the working relationship between the races. His work greatly helped blacks to achieve higher education, financial power, and understanding of the U.S. legal system. This contributed to blacks' attaining the skills to create and support the civil rights movement, leading to the passage of important federal civil rights laws.

Early life

Washington early in his career.

Booker was born into slavery to Jane, an enslaved African-American woman on the plantation of James Burroughs in southwest Virginia, near Hale's Ford in Franklin County. He never knew the day, month, and year of his birth,[7] but the year on his headstone reads 1856.[8] Nor did he ever know his father, said to be a white man who resided on a neighboring plantation. The man played no financial or emotional role in Washington's life.[9]

From his earliest years, the slave boy was known simply as "Booker," with no middle or surname, in the practice of the time.[10] His mother, her relatives and his siblings struggled with the demands of slavery. He later recalled that

I cannot recall a single instance during my childhood or early boyhood when our entire family sat down to the table together, and God's blessing was asked, and the family ate a meal in a civilized manner. On the plantation in Virginia, and even later, meals were gotten to the children very much as dumb animals get theirs. It was a piece of bread here and a scrap of meat there. It was a cup of milk at one time and some potatoes at another.[11]

When he was nine, Booker and his family in Virginia gained freedom under the Emancipation Proclamation as US troops occupied their region. Booker was thrilled by the formal day of their emancipation in early 1865:

As the great day drew nearer, there was more singing in the slave quarters than usual. It was bolder, had more ring, and lasted later into the night. Most of the verses of the plantation songs had some reference to freedom... Some man who seemed to be a stranger (a United States officer, I presume) made a little speech and then read a rather long paper—the Emancipation Proclamation, I think. After the reading we were told that we were all free, and could go when and where we pleased. My mother, who was standing by my side, leaned over and kissed her children, while tears of joy ran down her cheeks. She explained to us what it all meant, that this was the day for which she had been so long praying, but fearing that she would never live to see.[12]

After emancipation Jane took her family to West Virginia to join her husband Washington Ferguson, who had escaped from slavery and settled there during the war. There the illiterate boy Booker began to painstakingly teach himself to read and attended school for the first time.[13]

When he started school, Booker was faced with the need to provide a surname; he claimed the family name of Washington, after his stepfather.[10] Still later he learned from his mother that she had originally given him the name "Booker Taliaferro" at the time of his birth, with the second name instantly falling into disuse.[14] Upon learning of his original name, Washington immediately readopted it as his own, assuming the name he used for the rest of his life, Booker Taliaferro Washington.[14]

Higher education

Washington worked in salt furnaces and coal mines in West Virginia for several years to earn money. He made his way east to Hampton Institute, a school established to educate freedmen and their descendants, where he worked to pay for his studies.[citation needed] He also attended Wayland Seminary in Washington, D.C. in 1878 and left after 6 months.[citation needed]

Tuskegee Institute

Booker T. Washington's house at Tuskegee University

A history class conducted at the Tuskegee Institute in 1902

In 1881, the Hampton Institute president Samuel C. Armstrong recommended then-25-year-old Washington to become the first leader of Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute (later Tuskegee Institute, now Tuskegee University), the new normal school (teachers' college) in Alabama. The new school opened on July 4, 1881, initially using space in a local church. The next year, Washington purchased a former plantation, which became the permanent site of the campus. Under his direction, his students literally built their own school: making bricks, constructing classrooms, barns and outbuildings; and growing their own crops and raising livestock; both for learning and to provide for most of the basic necessities.[15] Both men and women had to learn trades as well as academics. Washington helped raise funds to establish and operate hundreds of small community schools and institutions of higher educations for blacks.[16][page needed] The Tuskegee faculty used all the activities to teach the students basic skills to take back to their mostly rural black communities throughout the South. The main goal was not to produce farmers and tradesmen, but teachers of farming and trades who taught in the new schools and colleges for blacks across the South. The school expanded over the decades, adding programs and departments, to become the present-day Tuskegee University.[17][page needed] He led the institution for the rest of his life, more than 30 years. As he developed it, adding to both the curriculum and the facilities on the campus, he became a prominent national leader among African Americans, with considerable influence with wealthy white philanthropists and politicians.

Washington expressed his vision for his race in his direction of the school. He believed that by providing needed skills to society, African Americans would play their part, leading to acceptance by white Americans. He believed that blacks would eventually gain full participation in society by acting as responsible, reliable American citizens. Shortly after the Spanish–American War, President William McKinley and most of his cabinet visited Booker Washington. He led the school until his death in 1915. By then Tuskegee's endowment had grown to over $1.5 million, compared to its initial $2,000 annual appropriation.[17][page needed][18][page needed]

Washington was instrumental in lobbying the state legislature in 1891 to locate the newly authorized West Virginia State University in the Kanawha Valley of West Virginia near Charleston. He visited the campus often and spoke at its first commencement exercise.[19]

Washington was a dominant figure of the African-American community, then still overwhelmingly based in the South, from 1890 to his death in 1915. His Atlanta Address of 1895 received national attention. He was considered as a popular spokesman for African-American citizens. Representing the last generation of black leaders born into slavery, Washington was generally perceived as a supporter of education for freedmen and their descendants in the post-Reconstruction, Jim Crow-era South through basic education and training in manual and domestic labor trades.[citation needed] Throughout the final twenty years of his life, he maintained his standing through a nationwide network of supporters including black educators, ministers, editors, and businessmen, especially those who supported his views on social and educational issues for blacks. He also gained access to top national white leaders in politics, philanthropy and education, raised large sums, was consulted on race issues, and was awarded honorary degrees from leading American universities.

Late in his career, Washington was criticized by civil rights leader and NAACP founder W. E. B. Du Bois. Du Bois and his supporters opposed the Atlanta Address as the "Atlanta Compromise", because it provided that African Americans should work for, and submit to, white political rule. Du Bois insisted on full civil rights, due process of law and increased political representation for African Americans which, he believed, could only be achieved through activism and higher education for African-Americans. Du Bois labeled Washington, "the Great Accommodator". Washington's response was that confrontation could lead to disaster for the outnumbered blacks and that cooperation with supportive whites was the only way to overcome racism in the long run.[citation needed]

While promoting moderation, Washington contributed secretly and substantially to mounting legal challenges against segregation and disenfranchisement of blacks.[5][page needed] In his public role, he believed he could achieve more by skillful accommodation to the social realities of the age of segregation.[20]

Washington's work on education problems helped him enlist both the moral and substantial financial support of many major white philanthropists. He became a friend of such self-made men as Standard Oil magnate Henry Huttleston Rogers; Sears, Roebuck and Company President Julius Rosenwald; and George Eastman, inventor of roll film, founder of Eastman Kodak, and developer of a major part of the photography industry. These individuals and many other wealthy men and women funded his causes, including Hampton and Tuskegee institutes.[citation needed]

He also gave lectures in support of raising money for the school. On January 23, 1906, he lectured at Carnegie Hall in New York in the Tuskegee Institute Silver Anniversary Lecture. He spoke along with great orators of the day including Mark Twain, Joseph Hodges Choate, and Robert Curtis Ogden; it was the start of a capital campaign to raise $1,800,000 for the school.[21]

The schools which Washington supported were founded primarily to produce teachers, as education was critical for the black community following emancipation. Freedmen strongly supported literacy and education as the keys to their future. When graduates returned to their largely impoverished rural southern communities, they still found few schools and educational resources, as the white-dominated state legislatures consistently underfunded black schools in their segregated system.[citation needed]

To address those needs, in the 20th century Washington enlisted his philanthropic network to create matching funds programs to stimulate construction of numerous rural public schools for black children in the South. Working especially with Julius Rosenwald from Chicago, Washington had Tuskegee architects develop model school designs. The Rosenwald Fund helped support the construction and operation of more than 5,000 schools and related resources for the education of blacks throughout the South in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The local schools were a source of communal pride; African-American families gave labor, land and money to them, to give their children more chances in an environment of poverty and segregation. A major part of Washington's legacy, the model rural schools continued to be constructed into the 1930s, with matching funds for communities from the Rosenwald Fund.[22][page needed]

Washington also contributed to the Progressive Era by forming the National Negro Business League. It encouraged entrepreneurship among black businessmen, establishing a national network.[22][page needed]

His autobiography, Up from Slavery, first published in 1901,[23] is still widely read in the early 21st century.

Marriages and children

Booker T. Washington with his third wife Margaret and two sons.

Washington was married three times. In his autobiography Up from Slavery, he gave all three of his wives credit for their contributions at Tuskegee. His first wife Fannie N. Smith was from Malden, West Virginia, the same Kanawha River Valley town where Washington had lived from age nine to sixteen. He maintained ties there all his life, and Smith was his student in Malden. He helped her gain entrance into the Hampton Institute, and Washington and Smith were married in the summer of 1882. They had one child, Portia M. Washington. Fannie died in May 1884.[17]

Washington next wed Olivia A. Davidson in 1885. Born in Virginia, she had studied at Hampton Institute and the Massachusetts State Normal School at Framingham. She taught in Mississippi and Tennessee before going to Tuskegee to work as a teacher. Washington met Davidson at Tuskegee, where she was promoted to assistant principal. They had two sons, Booker T. Washington Jr. and Ernest Davidson Washington, before she died in 1889.

In 1893 Washington married Margaret James Murray. She was from Mississippi and had graduated from Fisk University, a historically black college. They had no children together, but she helped rear Washington's three children. Murray outlived Washington and died in 1925.

Politics and the Atlanta compromise

"The Atlanta Compromise"

MENU0:00

The opening of Booker T. Washington's "Atlanta compromise" speech to the Atlanta Cotton States and International Exposition

Problems playing this file? See media help.

Washington circa 1895, by Frances Benjamin Johnston

Washington's 1895 Atlanta Exposition address was viewed as a "revolutionary moment"[24] by both African Americans and whites across the country. At the time W. E. B. Du Bois supported him, but they grew apart as Du Bois sought more action to remedy disfranchisement and improve educational opportunities for blacks. After their falling out, Du Bois and his supporters referred to Washington's speech as the "Atlanta Compromise" to express their criticism that Washington was too accommodating to white interests.

Washington advocated a "go slow" approach to avoid a harsh white backlash.[24] The effect was that many youths in the South had to accept sacrifices of potential political power, civil rights and higher education.[25] His belief was that African Americans should "concentrate all their energies on industrial education, and accumulation of wealth, and the conciliation of the South".[26] Washington valued the "industrial" education, as it provided critical skills for the jobs then available to the majority of African Americans at the time, as most lived in the South, which was overwhelmingly rural and agricultural. He thought these skills would lay the foundation for the creation of stability that the African-American community required in order to move forward. He believed that in the long term, "blacks would eventually gain full participation in society by showing themselves to be responsible, reliable American citizens". His approach advocated for an initial step toward equal rights, rather than full equality under the law, gaining economic power to back up black demands for political equality in the future.[27] He believed that such achievements would prove to the deeply prejudiced white America that African Americans were not "'naturally' stupid and incompetent".[28]

Washington giving a speech at Carnegie Hall in New York City, 1909

Well-educated blacks in the North advocated a different approach, in part due to the differences they perceived in opportunities. Du Bois wanted blacks to have the same "classical" liberal arts education as upscale whites did,[29] along with voting rights and civic equality, the latter two elements granted since 1870 by constitutional amendments after the Civil War. He believed that an elite, which he called the Talented Tenth, would advance to lead the race to a wider variety of occupations.[30] Du Bois and Washington were divided in part by differences in treatment of African Americans in the North versus the South; although both groups suffered discrimination, the mass of blacks in the South were far more constrained by legal segregation and exclusion from the political process. Many in the North objected to being 'led', and authoritatively spoken for, by a Southern accommodationist strategy which they considered to have been "imposed on them [Southern blacks] primarily by Southern whites".[31] Historian Clarence Earl Walker wrote that, for white Southerners,

Free black people were 'matter out of place'. Their emancipation was an affront to southern white freedom. Booker T. Washington did not understand that his program was perceived as subversive of a natural order in which black people were to remain forever subordinate or unfree.[32]

Both Washington and Du Bois sought to define the best means to improve the conditions of the post-Civil War African-American community through education.

Blacks were solidly Republican in this period, having gained emancipation and suffrage with the President Lincoln and his party and later fellow Republican President Ulysses S. Grant defending African American's newly won freedom and civil rights in the South during Reconstruction. After Federal troops left, Southern states disfranchised most blacks and many poor whites from 1890–1908 through constitutional amendments and statutes that created barriers to voter registration and voting, such as poll taxes and literacy tests. By the late nineteenth century, Southern white Democrats defeated some biracial Populist-Republican coalitions and regained power in the state legislatures of the former Confederacy; they passed laws establishing racial segregation and Jim Crow. In the border states and North, blacks continued to exercise the vote; the well-established Maryland African-American community defeated attempts there to disfranchise them.

Washington worked and socialized with many national white politicians and industry leaders. He developed the ability to persuade wealthy whites, many of them self-made men, to donate money to black causes by appealing to values they had exercised in their rise to power. He argued that the surest way for blacks to gain equal social rights was to demonstrate "industry, thrift, intelligence and property".[33] He believed these were key to improved conditions for African Americans in the United States. Because African Americans had only recently been emancipated and most lived in a hostile environment, Washington believed they could not expect too much at once. He said, "I have learned that success is to be measured not so much by the position that one has reached in life as by the obstacles which he has had to overcome while trying to succeed."[17][page needed]

Along with Du Bois, Washington partly organized the "Negro exhibition" at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris, where photos of Hampton Institute's black students were displayed. These were taken by his friend Frances Benjamin Johnston.[34] The exhibition demonstrated African Americans' positive contributions to United States' society.[34]

Washington privately contributed substantial funds for legal challenges to segregation and disfranchisement, such as the case of Giles v. Harris, which was heard before the United States Supreme Court in 1903.[35][page needed] Even when such challenges were won at the Supreme Court, southern states quickly responded with new laws to accomplish the same ends, for instance, adding "grandfather clauses" that covered whites and not blacks.

Wealthy friends and benefactors

Washington's wealthy friends included Andrew Carnegie and Robert Curtis Ogden, seen here in 1906 while visiting Tuskegee Institute.

State and local governments gave little money to black schools, but white philanthropists proved willing to invest heavily. Washington encouraged them and directed millions of their money to projects all across the South that Washington thought best reflected his self-help philosophy. Washington associated with the richest and most powerful businessmen and politicians of the era. He was seen as a spokesperson for African Americans and became a conduit for funding educational programs.

His contacts included such diverse and well-known entrepreneurs and philanthropists as Andrew Carnegie, William Howard Taft, John D. Rockefeller, Henry Huttleston Rogers, George Eastman, Julius Rosenwald, Robert Curtis Ogden, Collis Potter Huntington, and William Henry Baldwin Jr.. The latter donated large sums of money to agencies such as the Jeanes and Slater Funds. As a result, countless small rural schools were established through his efforts, under programs that continued many years after his death. Along with rich white men, the black communities helped their communities directly by donating time, money, and labor to schools in a sort of matching fund.[36]

Henry Huttleston Rogers

Handbill from 1909 tour of southern Virginia and West Virginia.

A representative case of an exceptional relationship was Washington's friendship with millionaire industrialist and financier Henry H. Rogers (1840–1909). Henry Rogers was a self-made man, who had risen from a modest working-class family to become a principal officer of Standard Oil, and one of the richest men in the United States. Around 1894 Rogers heard Washington speak at Madison Square Garden. The next day he contacted Washington and requested a meeting, during which Washington later recounted that he was told that Rogers "was surprised that no one had 'passed the hat' after the speech."[citation needed] The meeting began a close relationship that was to extend over a period of 15 years. Although Washington and the very-private Rogers were seen by the public as friends, the true depth and scope of their relationship was not publicly revealed until after Rogers' sudden death of a stroke in May 1909. Washington was a frequent guest at Rogers' New York office, his Fairhaven, Massachusetts summer home, and aboard his steam yacht Kanawha.

A few weeks later Washington went on a previously planned speaking tour along the newly completed Virginian Railway, a $40-million enterprise which had been built almost entirely from Rogers' personal fortune. As Washington rode in the late financier's private railroad car, Dixie, he stopped and made speeches at many locations, where his companions later recounted that he had been warmly welcomed by both black and white citizens at each stop.[citation needed]

Washington revealed that Rogers had been quietly funding operations of 65 small country schools for African Americans, and had given substantial sums of money to support Tuskegee and Hampton institutes. He also disclosed that Rogers had encouraged programs with matching funds requirements so the recipients had a stake in the outcome.[citation needed]

Anna T. Jeanes

In 1907 Philadelphia Quaker Anna T. Jeanes (1822–1907) donated one million dollars to Washington for elementary schools for black children in the South. Her contributions and those of Henry Rogers and others funded schools in many poor communities.

Julius Rosenwald

Julius Rosenwald (1862–1932) was another self-made wealthy man with whom Washington found common ground. By 1908 Rosenwald, son of an immigrant clothier, had become part-owner and president of Sears, Roebuck and Company in Chicago. Rosenwald was a philanthropist who was deeply concerned about the poor state of African-American education, especially in the Southern states, where their schools were underfunded.[37]

The collaboration between Booker T. Washington and Julius Rosenwald, who was Jewish, was the subject of the 2015 documentary Rosenwald, subtitled[38] A Remarkable Story of a Jewish Partnership with African American Communities by writer, producer and director Aviva Kempner,[39][40] which won Best Documentary Jury Award at the Teaneck International Film Festival and the Lipscomb University Prize of the Ecumenical Jury, Nashville Film Festival.[38]

In 1912 Rosenwald was asked to serve on the Board of Directors of Tuskegee Institute, a position he held for the remainder of his life. Rosenwald endowed Tuskegee so that Washington could spend less time fundraising and more managing the school. Later in 1912 Rosenwald provided funds for a pilot program to build six new small schools in rural Alabama. They were designed, constructed and opened in 1913 and 1914 and overseen by Tuskegee; the model proved successful. Rosenwald established the Rosenwald Fund. The school building program was one of its largest programs. Using architectural model plans developed by professors at Tuskegee Institute, the Rosenwald Fund spent over $4 million to help build 4,977 schools, 217 teachers' homes, and 163 shop buildings in 883 counties in 15 states, from Maryland to Texas.[41] The Rosenwald Fund made matching grants, requiring community support, cooperation from the white school boards, and fundraising. Black communities raised more than $4.7 million to aid the construction; essentially they taxed themselves twice to do so.[42] These schools became informally known as Rosenwald Schools. By 1932, the facilities could accommodate one third of all African-American children in Southern U.S. schools.

Up from Slavery to the White House

Booker Washington and Theodore Roosevelt at Tuskegee Institute, 1905

Washington's long-term adviser, Timothy Thomas Fortune (1856–1928), was a respected African-American economist and editor of The New York Age, the most widely read newspaper in the black community within the United States. He was the ghost-writer and editor of Washington's first autobiography, The Story of My Life and Work.[43] Washington published five books during his lifetime with the aid of ghost-writers Timothy Fortune, Max Bennett Thrasher and Robert E. Park.[44]

They included compilations of speeches and essays:

The Story of My Life and Work (1900)

Up from Slavery (1901)

The Story of the Negro: The Rise of the Race from Slavery (2 vol 1909)

My Larger Education (1911)

The Man Farthest Down (1912)

In an effort to inspire the "commercial, agricultural, educational, and industrial advancement" of African Americans, Washington founded the National Negro Business League (NNBL) in 1900.[45]

When Washington's second autobiography, Up from Slavery, was published in 1901, it became a bestseller and had a major effect on the African-American community, its friends and allies. In October 1901, President Theodore Roosevelt invited Washington to dine with him and his family at the White House; he was the first African American to be invited there by a president. Democratic Party politicians from the South, including future Governor of Mississippi James K. Vardaman and Senator Benjamin Tillman of South Carolina indulged in racist personal attacks when they learned of the invitation. Vardaman described the White House as

so saturated with the odor of the nigger that the rats have taken refuge in the stable,[46][47] and declared "I am just as much opposed to Booker T. Washington as a voter as I am to the cocoanut-headed, chocolate-colored typical little coon who blacks my shoes every morning. Neither is fit to perform the supreme function of citizenship."[48]

Tillman said, "The action of President Roosevelt in entertaining that nigger will necessitate our killing a thousand niggers in the South before they will learn their place again."[49]

Austro-Hungarian ambassador to the United States Ladislaus Hengelmüller von Hengervár, who was visiting the White House on the same day, claimed to have found a rabbit's foot in Washington's coat pocket when he mistakenly put on the coat. The Washington Post elaborately described it as "the left hind foot of a graveyard rabbit, killed in the dark of the moon".[50] The Detroit Journal quipped the next day, "The Austrian ambassador may have made off with Booker T. Washington's coat at the White House, but he'd have a bad time trying to fill his shoes."[50][51]

Death

Booker T. Washington's coffin being carried to grave site.

Despite his travels and widespread work, Washington remained as principal of Tuskegee. Washington's health was deteriorating rapidly in 1915; he collapsed in New York City and was diagnosed by two different doctors as having Bright's disease. Told he only had a few days left to live, Washington expressed a desire to die at Tuskegee. He boarded a train and arrived in Tuskegee shortly after midnight on November 14, 1915, and he died a few hours later at the age of 59.[52] He was buried on the campus of Tuskegee University near the University Chapel.

His death was believed at the time to have been a result of congestive heart failure, aggravated by overwork. In March 2006, with the permission of his descendants, examination of medical records indicated that he died of hypertension, with a blood pressure more than twice normal, confirming what had long been suspected.[53]

At his death Tuskegee's endowment was close to $2 million.[54] Washington's greatest life's work, the education of blacks in the South, was well underway and expanding.

Honors and memorials

Main article: List of things named after Booker T. Washington

For his contributions to American society, Washington was granted an honorary master's degree from Harvard University in 1896 and an honorary doctorate from Dartmouth College in 1901.

At the end of the 2008 presidential election, the defeated Republican candidate, Senator John McCain, recalled the outrage that Booker Washington's visit to Theodore Roosevelt's White House a century before, caused. McCain pointed out the evident progress the country had made since that event: Barack Obama was elected as the first African-American President of the United States.[55]

In 1934 Robert Russa Moton, Washington's successor as president of Tuskegee University, arranged an air tour for two African-American aviators. Afterward he had the plane named the Booker T. Washington.[56]

Booker T. Washington was honored on a 'Famous Americans Series' Commemorative U.S. Postage stamp, issue of 1940.

On April 7, 1940, Washington became the first African American to be depicted on a United States postage stamp. Several years later, he was honored on the first coin to feature an African American, the Booker T. Washington Memorial Half Dollar, which was minted by the United States from 1946 to 1951. He was also depicted on a U.S. Half Dollar from 1951–1954.[57]

In 1942, the liberty ship Booker T. Washington was named in his honor, the first major oceangoing vessel to be named after an African American. The ship was christened by Marian Anderson.[58]

On April 5, 1956, the hundredth anniversary of Washington's birth, the house where he was born in Franklin County, Virginia, was designated as the Booker T. Washington National Monument.

A state park in Chattanooga, Tennessee, was named in his honor, as was a bridge spanning the Hampton River adjacent to his alma mater, Hampton University.

In 1984 Hampton University dedicated a Booker T. Washington Memorial on campus near the historic Emancipation Oak, establishing, in the words of the University, "a relationship between one of America's great educators and social activists, and the symbol of Black achievement in education."[59]

Numerous high schools, middle schools and elementary schools[60] across the United States have been named after Booker T. Washington.

At the center of the campus at Tuskegee University, the Booker T. Washington Monument, called Lifting the Veil, was dedicated in 1922. The inscription at its base reads:

He lifted the veil of ignorance from his people and pointed the way to progress through education and industry.

In 2000, West Virginia State University (WVSU; then West Va. State College), in cooperation with other organizations including the Booker T. Washington Association, established the Booker T. Washington Institute, to honor Washington's boyhood home, the old town of Malden, and the ideals Booker Washington stood for.[61]

On October 19, 2009, WVSU dedicated a monument to the memory of noted African American educator and statesman Booker T. Washington. The event took place at West Virginia State University's Booker T. Washington Park in Malden, West Virginia. The monument also honors the families of African ancestry who lived in Old Malden in the early 20th century and who knew and encouraged Booker T. Washington. Special guest speakers at the event included West Virginia Governor Joe Manchin III, Malden attorney Larry L. Rowe, and the president of WVSU. Musical selections were provided by the WVSU "Marching Swarm."[62]

Legacy

Sculpture of Booker T. Washington at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.

Washington was held in high regard by business-oriented conservatives, both white and black. Historian Eric Foner argues that the freedom movement of the late nineteenth century changed directions so as to align with America's new economic and intellectual framework. Black leaders emphasized economic self-help and individual advancement into the middle class as a more fruitful strategy than political agitation. There was emphasis on education and literacy throughout the period after the Civil War. Washington's famous Atlanta speech of 1895 marked this transition, as it called on blacks to develop their farms, their industrial skills and their entrepreneurship as the next stage in emerging from slavery.

By this time, Mississippi had passed a new constitution, and other southern states were following suit, or using electoral laws to raise barriers to voter registration; they completed disenfranchisement of blacks to maintain white supremacy. At the same time, Washington secretly arranged to fund numerous legal challenges to voting restrictions and segregation.[1]

Washington repudiated the abolitionist emphasis on unceasing agitation for full equality, advising blacks that it was counterproductive to fight segregation at that point. Foner concludes that Washington's strong support in the black community was rooted in its widespread realization that frontal assaults on white supremacy were impossible, and the best way forward was to concentrate on building up the economic and social structures inside segregated communities.[63] Historian C. Vann Woodward said of Washington, "The businessman's gospel of free enterprise, competition, and laissez faire never had a more loyal exponent."[64]

Historians since the late 20th century have been divided in their characterization of Washington: some describe him as a visionary capable of "read[ing] minds with the skill of a master psychologist," who expertly played the political game in 19th-century Washington by its own rules.[3] Others say he was a self-serving, crafty narcissist who threatened and punished those in the way of his personal interests, traveled with an entourage, and spent much time fundraising, signing autographs, and giving flowery patriotic speeches with lots of flag waving — acts more indicative of an artful political boss than an altruistic civil rights leader.[3]

People called Washington the "Wizard of Tuskegee" because of his highly developed political skills, and his creation of a nationwide political machine based on the black middle class, white philanthropy, and Republican Party support. Opponents called this network the "Tuskegee Machine." Washington maintained control because of his ability to gain support of numerous groups, including influential whites and the black business, educational and religious communities nationwide. He advised on the use of financial donations from philanthropists, and avoided antagonizing white Southerners with his accommodation to the political realities of the age of Jim Crow segregation.[20]

Descendants

Washington's first daughter by Fannie, Portia Marshall Washington (1883-1978), was a trained pianist who married Tuskegee educator and architect William Sidney Pittman in 1900, with whom she had three children. However, Pittman faced several difficulties in trying to ply his trade while his wife built her musical profession. Eventually, when Pittman assaulted their daughter Fannie in the midst of an argument, Portia took Fannie and left Pittman to resettle at Tuskegee. She was removed from the faculty in 1939 for not having an academic degree, but she opened her own piano teaching practice for a few years. After retiring in 1944 at the age of 61, she dedicated her efforts in the 1940s to memorializing her father, succeeding in getting her father's bust placed in the Hall of Fame in New York, his face being placed on the fifty-cent coin and his Virginia birthplace being declared a national monument. Portia died on February 26, 1978, in Washington, D.C.[65].